Imagine you are standing waist-deep in a green ocean…

It is not an ocean of water, but one of plants. The flowers appear like yellow, purple, white, pink, orange, and periwinkle confetti, bobbing on the surface of the waves.

Your feet are touching the cool Earth, which smells sweet and moist. A warm breeze tousles your hair and caresses the landscape, sending ripples and waves through the grass. Below the surface of the waves of green grasses, last season’s dry plants rustle stiffly, propping up the new growth to bounce back against the wind.

You hear and feel the vibration of tiny wings–there are bees of all shapes, sizes, and patterns buzzing and wrestling with the pollen inside of so many flowers, all around you. A butterfly flaps its spotted wings, its attention drawn from one fragrant flower, to the next, and the next. You hear a cardinal whistle in a distant tree. A squadron of sparrows squabble over seeds in the brush.

You are a small human adrift in this vibrant ecosystem called a prairie.

What is a prairie?

Prairies are a grassland ecosystem made predominantly of herbaceous plants. This includes grasses and forbs (another name for the native flowering plants of the prairie), both of which have extensive root systems which grow deep into the ground and can comprise up to 75% of a plant’s total biomass. Trees may be present, but when they are they’re few and far between, usually hugging more protected sites along creeks and rivers.

Historically, prairies supported massive populations of animals, too. Many researchers estimate between 30-60 million bison roamed the North American prairies before 1840, as well as deer, elk, antelope, gophers, prairie dogs, squirrels, voles and other rodents, and the predators that hunted them, grizzly bears, panthers, and wolves. Countless native and migratory bird species live in the prairies, too. Not to mention the insects. Bees are hugely important to the prairie ecosystem, as forbs rely on them for pollination. 1

While grasses are typically wind pollinated, forbs rely on pollinators to reproduce. Bees, butterflies, moths, beetles, and wasps all help pollinate prairie plants. Other insects are a beneficial and symbiotic part of this ecosystem too, such as ants, spiders, and beetles—not only are they meals for larger mammals and birds, they also burrow into the ground, aerating the soil and bringing nutrients from deep in the soil upward where plants can use them.

Millions of bacteria and fungi are at work in the soil, composting decaying plant matter and other organisms. The decomposed nutrient elements, such as carbon and nitrogen, are then stored in the soil until taken back in through the plant roots. Dense masses of roots form a woven lattice called sod, which acts like a giant sponge catching and holding rainwater. The sod also binds the soil to the Earth, protecting it from washing or blowing away from the forces of water and wind.

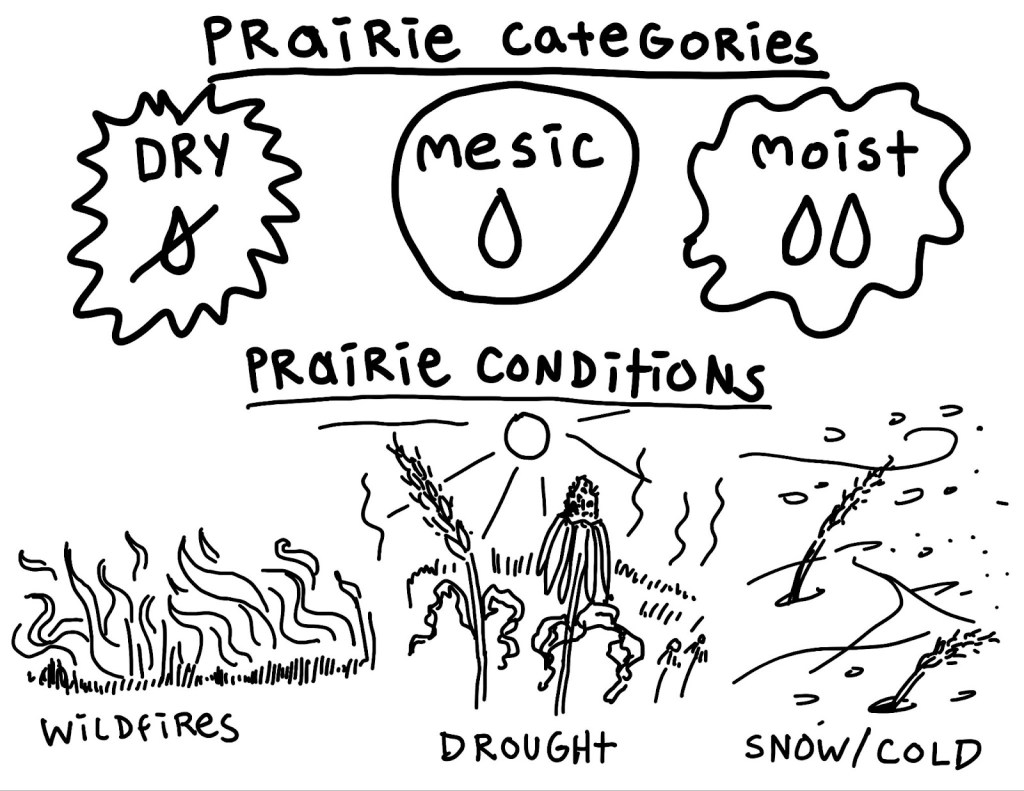

Moreover, there are dozens of types of prairies, each thriving in a unique microclimate with unique flora and fauna. Prairies are usually described using either the term moist, dry, or mesic. Moist prairies may be in wetlands or areas that flood and stay moist most of the year. Dry prairies do without water for the vast majority of a year. Mesic prairies get rain, become wet, then dry out.2

Prairies are resilient. They live in some of the most extreme conditions on both ends of the temperature and precipitation spectrum. They must survive long periods of drought and heat in excess of 100 degrees Fahrenheit in the summer, including wildfires that turn all above-ground plants to ash, leaving only the root systems, while also be able to withstand frozen soil, the piling of feet of snow, and bitter cold temperatures and wind in the winter. But plants that were able to survive those conditions succeeded in Illinois and became very common, leading to the state being covered in prairie ecosystems.

But prairies were not always in Illinois, or in North America.

From the Ice Age to the Prairie State

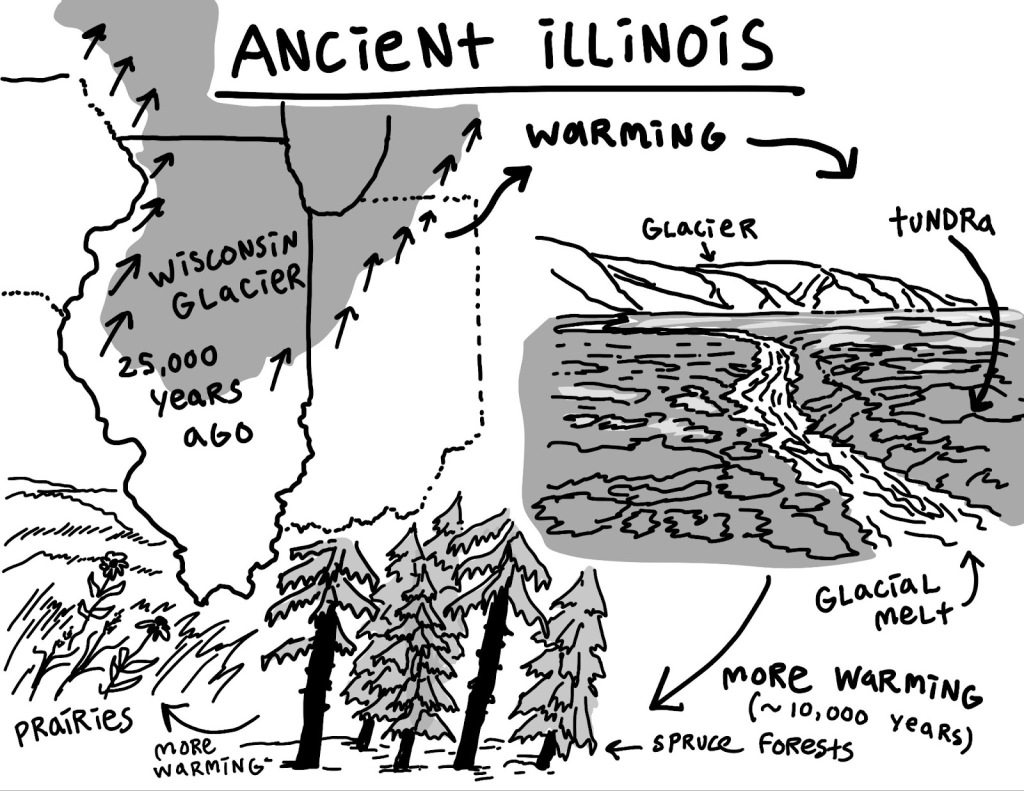

25,000 years ago, the Ice Age was ending and this land was changing drastically. As the climate warmed, the Wisconsin glacier melted in the summer, froze again in the winter, and each successive summer melted a little more. With each warm season the glacial melt released outwash, depositing sediments and silt across the Illinois ground. Hills called moraines were created by the force of the glacier’s edge, which pushed and piled up rocks, clay, and debris.3

At first, the glacier’s retreat led to the growth of a tundra-type ecosystem, then large spruce forests. As the climate warmed even further, tundra and spruce forests gave way to prairie and oak woodlands, and grasses and forbs evolved to survive in this fertile and polarized ecosystem. Their deep roots allowed them to survive wildfires, the trampling hooves of large grazing mammals, and the winter’s cold and snow. Bison, elk, and deer foraged on the plants, and drove their seeds deeper into the ground with their hooves helping them propagate. Fires swept through, destroying dying or dead plant matter and wiping out any tree competition except that of hearty, mature oaks, whose thick bark defended them from the fire. With roots intact and the soil newly fertilized with burned matter, the plants could put out new green growth out of their roots with little competition.

This new ecosystem started to evolve over twenty millennia ago. Since about 8,300 years ago, prairies were THE dominant land type in the central North American plains–an ocean of grass and flowers. And for all that time, the prairie sustained human societies as well, the Lakota, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Potawatomi, Shawnee, Osage, Kiowa, Peoria, Cahokia, Kaskaskia, Tamaroa, Miami, Kickapoo, Sauk, Winnebago, many more, and their distant, distant ancestors.4 In fact, to this day, Illinois is known as the Prairie State.

Why are there no more prairies in the Prairie State?

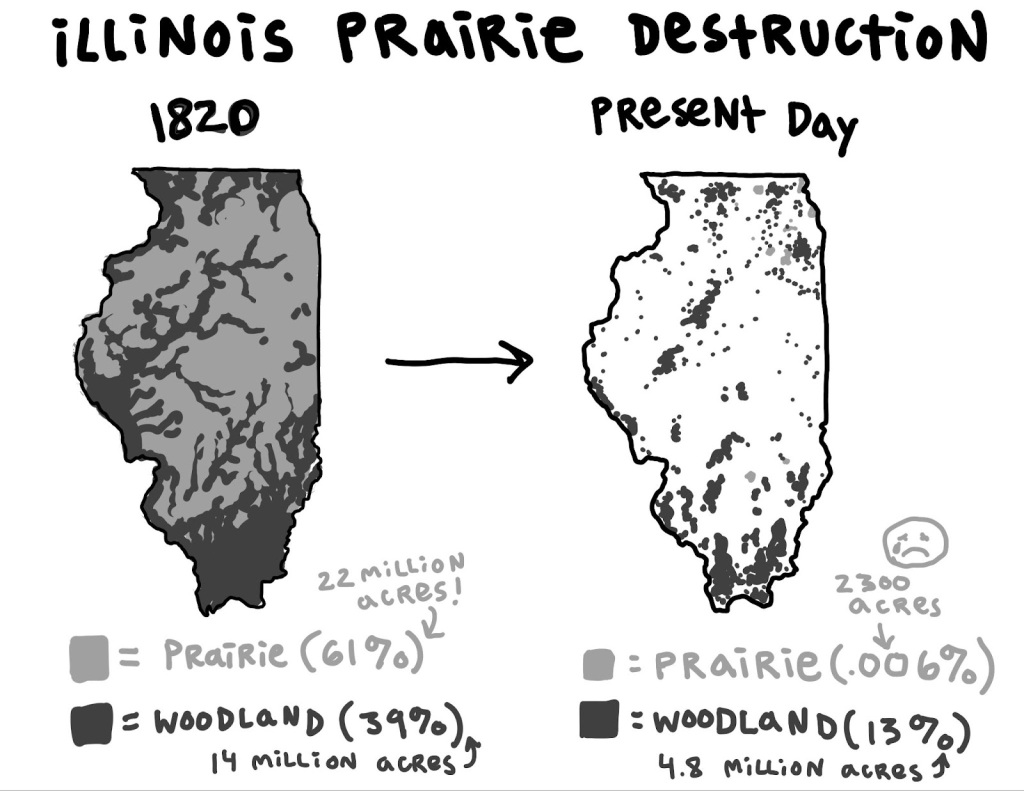

When Illinois became a U.S. state in 1818, it had 22 million acres of prairie grasslands and 14 million acres of forests. Now, only .006% of the original prairies remain.5

European settlers came to Illinois and all over the U.S., divided it up into tracts, sold it, and developed the land for grazing and especially farming on the rich topsoil. The U.S. Government passed the 1830 Indian Removal Act, deporting the original stewards of the prairie from their ancestral lands, and then granted the land to large corporations and moneyed interests – for example, in 1851, the U.S. government granted 2.5 million acres (11%) of prairie land to the Illinois Central Railroad.6

Corn planting in Illinois currently uses about 11 million acres.7 Soybean planting makes up another 10.8 million acres.8 Much of the corn and soy we grow doesn’t feed humans but is used for animal feed for the pork and beef industry, as well as to create other corn and soy products like oils, syrups, inks, and ethanol so we can fuel up our cars and go visit the now less than 2,300 acres of high-quality prairie left in the state.

What’s more, the tilling and development of the prairies was not just to make land suitable FOR white settlers to farm and build on, but it was also to take nourishing, community-sustaining land AWAY from Indigenous people. The prairie was the grazing place of the bison, a major food and raw material source for nomadic plains peoples. In hunting the bison and burning the prairie, settlers made it very difficult for Indigenous people to live as they traditionally had. The legacy of plundering the prairies is not just about misunderstanding a biodiverse and important ecosystem! The destruction of prairies is also rooted in racism and genocide.

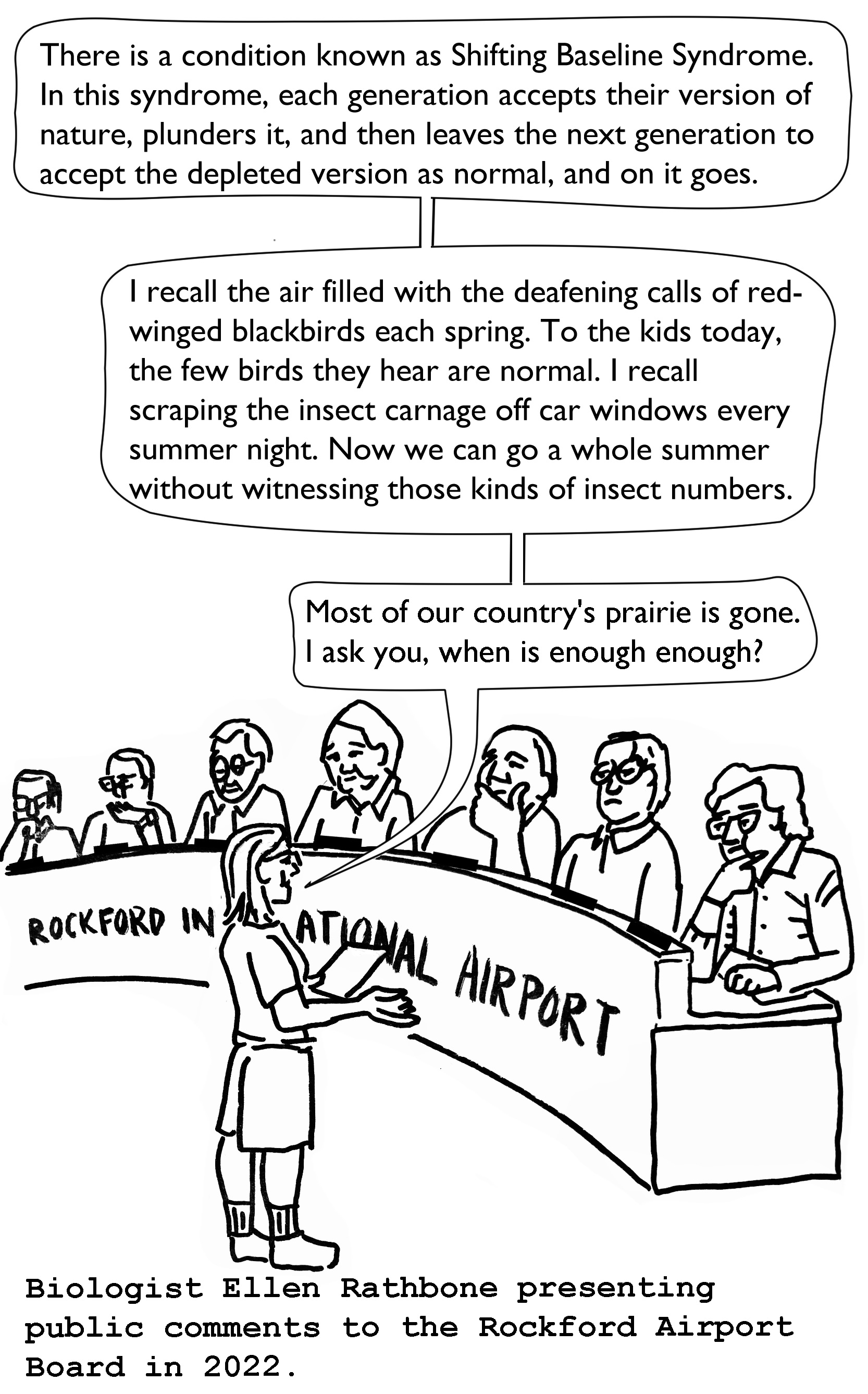

Fast forward to 2023 and prairie destruction in the name of development is still happening, even with only 2,300 acres of high quality prairie left in the state. In 2019 there was a proposed expansion to the Rockford, IL freight airport, to accommodate more trucks and runways to serve particularly Amazon and UPS freight companies. Environmental activists were able to halt construction for two years due to fears about destroying a unique gravel prairie known as the Bell Bowl Prairie, home to the endangered rusty-patched bumblebee. The activists won an injunction, stopping the construction. However, the Federal Aviation Administration eventually ruled that the construction could take place. Some of the highest quality acreage of Bell Bowl Prairie was bulldozed in 2023 to build an access road to the airport.9

Ecological grief

“To explain how ecological grief feels to many of us, I ask you to think of a pet you loved. When this pet passed away, you felt sadness and grieved their passing… For Indigenous peoples, we have these similar feelings but not just for our pets; we also have it for other plants and animals that are a part of our environments.”10

Dr. Jessica Hernandez, a Maya Ch’orti and Zapotec environmental scientist

We don’t often talk about grief in the conservation world. That’s because U.S. Conservation was begun by settler colonials, and still to this day views land as a commodity rather than a family member.

For those of us who don’t know the plants and animals around us, ecological grief can feel like estrangement from nature. It can feel like powerlessness as an individual to do anything to stop environmental degradation. After all, the 22 million acres of prairie are already destroyed, and we can’t just take it back, right?

We can take, and give, land back. There are ways we can fight, right in our front yards, to protect existing, and plant new prairies. Let our grief move us into action:

Let grief move down / To the earth / Down into the sickened soil / Through the bodies of worms / Pill bugs and ants / Out of our meaty shells / To make compost / Rich and ready / For new things to come

Sofia Salazar

To be clear, “land back” isn’t about us all going out and hugging trees. According to The Red Nation, “It is a serious agenda for decolonization that requires comprehensive land-return programs and funding for mass, Indigenous-led land restoration projects.”11 Healing the land (and ourselves) is ultimately about replacing infrastructures of capitalism with infrastructures of caretaking. By centering the knowledge and histories of Indigenous folks, together we will bring biodiverse ecosystems back.

Because of assimilation to a homogeneous U.S. culture, many European-Americans have lost touch with plants and land that once nurtured their ancestors and culture. Some of those nurturing plants from Europe are now labeled invasive in the Americas, having been introduced by settlers during colonial times, but they are nevertheless our plant relatives. Restoring land means understanding where invasive species belong, and whether and why to remove them.

What is a lawn?

Lawns are not native to Illinois, nor to the Americas. Both in terms of the species of grass and style of landscaping, lawns originate from Europe. In the 1200s, short lawns were cultivated around castles to make them more sightly (i.e. to make it possible to spot enemies from a distance). From serving a function of defense, lawns became a symbol of wealth. By the 1500s, lawns were popular in the formal gardens of the wealthy across western and northern Europe. Rich French and English colonizers brought lawns to North America, mimicking literature and paintings of European landscaping, using European grass species like bluegrass.12

After World War II, lawns became the default domestic landscape. The development of the suburbs played a major part in this spread, as developers purchased land just outside cities and built standardized tract houses with lawns to imitate the upper-class aesthetic. The chemical industry began re-marketing its surplus war supplies, such as nitrogen and DDT, for use as lawn fertilizers and pesticides. The mass production of lawn mowers made lawn maintenance feasible for working class folks. Social pressure from neighbors, homeowners associations, the city and state made it mandatory.13

In short, lawns have become a means of upholding capitalist values of respectability and consumerism. We are forced into a parasitic relationship with this manicured lawn, which supplants native ecosystems and will not heal our ecological grief. Lawns are a function of mass human disconnect with nature.

Prairies over lawns

Prairies are active resisters against capitalist society. They do not earn money or accrue equity. Like lawns, they are made of grasses, but they are tall grasses, and forbs, of many varieties. They are an autonomous biome without need for external inputs like fertilizers. They do not take an hour to install from a roll of sod; they take years to grow. They attract bugs, birds, rodents, and other wildlife. Prairies are always changing from month to month and year to year, and they provide free beauty and wonder to anyone who passes by.

There’s a growing number of people saying goodbye to lawns and planting beautiful, biodiverse prairies. Some people are hiring landscapers to remove their grass and sow all new seeds. Others are starting small and planting prairie plants in mulched-off parts of the yard. You can do this landscaping yourself! If you face social pressure against doing this kind of ecological restoration, such as from an HOA or municipal ordinance, organize with your neighbors and fight back.

Close your eyes and imagine the prairie we visualized earlier. The cheeps of birds overhead and deep in the underbrush. The warmth of the breeze. The sound of the rustling leaves in the wind. The aroma of flowers and the sweet smell of soil. Imagine all of your neighbors have a parkway or front yard full of the prairie. The path between your homes is a trail through an undulating ocean of sweet-smelling grasses and flowers, connecting you to neighbors and friends.

This is a meditation exercise. But this is also a real place. You can visit it! It’s part of our present. And we believe it’s our future.

Written and illustrated by Keith Couture and Hana Silverstein

- https://xerces.org/sites/default/files/2018-05/13-003_02_XercesSoc_Pollinators-in-Natural-Areas_web.pdf ↩︎

- https://publish.illinois.edu/tallgrass-prairie/ ↩︎

- https://experts.illinois.edu/en/publications/quaternary-glaciations-in-illinois ↩︎

- https://native-land.ca/ ↩︎

- https://dnr.illinois.gov/education/atoz/ilprairies.html ↩︎

- (https://www.museum.state.il.us/OHIA/htmls/people/early/peo_early.html) ↩︎

- https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Illinois/Publications/Current_News_Release/2023/20231109-IL-November-Crop-Production.pdf ↩︎

- https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Illinois/Publications/Current_News_Release/2023/20230112-IL-Annual-Crop-Production.pdf ↩︎

- https://www.savebellbowlprairie.org/ ↩︎

- Hernandez, Jessica. Fresh Banana Leaves. North Atlantic Books, 2022. ↩︎

- The Red Nation. The Red New Deal: Indigenous Action to Save Our Earth. Common Notions, 2021. ↩︎

- https://turf.umn.edu/sites/turf.umn.edu/files/2023-02/16_-_a_very_brief_history_of_lawns_-_01-30-23.pdf ↩︎

- https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/plants-in-the-classroom-the-story-of-oklahoma-turfgrass.html ↩︎